About Duke Slater

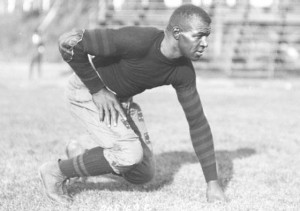

Duke Slater was the greatest African-American football player of the first half of the twentieth century. There are so many facets and aspects to his contributions to American sports that it seems impossible to cover them all. But in this brief Duke Slater biography, I’m going to try to give you a quick overview of one of the most remarkable athletes in American sports history.

Duke Slater

Frederick Wayman Slater was born on December 19, 1898, the oldest of six children born to George and Letha Slater. As a boy, Fred Slater somehow picked up the name of the family dog, Duke, as a personal nickname. Duke Slater learned the game of football playing neighborhood pickup games in the rough streets of the South Side of Chicago. While other boys enjoyed carrying the football, Slater loved to tackle, and since every football game needs linemen, Slater was assured of finding a spot in a street game wherever he went.

Frederick Wayman Slater was born on December 19, 1898, the oldest of six children born to George and Letha Slater. As a boy, Fred Slater somehow picked up the name of the family dog, Duke, as a personal nickname. Duke Slater learned the game of football playing neighborhood pickup games in the rough streets of the South Side of Chicago. While other boys enjoyed carrying the football, Slater loved to tackle, and since every football game needs linemen, Slater was assured of finding a spot in a street game wherever he went.

His father, George Slater, was a prominent, nationally-recognized African-American minister. When Duke was 13 years old, George became the pastor of a church in Clinton, Iowa. George initially forbade Duke from going out for football at Clinton High School, because he didn’t want Duke injured in the rough sport, a refrain still heard from parents over a century later. As a result, Duke didn’t play football as a freshman and would only play three seasons of high school football.

Before his sophomore year of high school, Duke joined the football team without his father’s knowledge. George Slater discovered his son’s football career when he saw his wife sewing up the rips in the ragged uniform that had been issued to Duke. George insisted that Duke quit the team, and a brokenhearted Duke went on a hunger strike for several days in protest. Finally, his father acquiesced on the condition that Duke must be careful to avoid injury. Because of that, Duke was always careful to never complain or let anyone see his injuries. His habit of concealing his injuries – combined with his massive strength – would give him an aura of invincibility as his football career progressed. George Slater would eventually become one of Duke’s biggest fans.

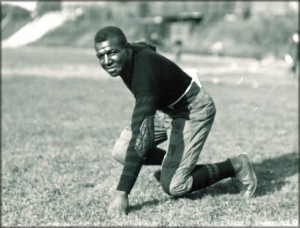

The Slater family was extremely poor, a fact conspicuously illustrated when he joined the Clinton High School team as a sophomore in 1913. At that time, students had to pay for their own helmets and shoes, but Duke’s family could not afford both. George told Duke to pick one or the other, and Duke decided he needed shoes more. He played his entire high school football career and most of his college career without a helmet. Meanwhile, Duke’s feet were so big, his shoes had to be special ordered from Chicago.

The Slater family was extremely poor, a fact conspicuously illustrated when he joined the Clinton High School team as a sophomore in 1913. At that time, students had to pay for their own helmets and shoes, but Duke’s family could not afford both. George told Duke to pick one or the other, and Duke decided he needed shoes more. He played his entire high school football career and most of his college career without a helmet. Meanwhile, Duke’s feet were so big, his shoes had to be special ordered from Chicago.

Duke Slater developed into a powerful lineman at the tackle position. He played well for Clinton High, leading them to two mythical state championships in 1913 and 1914. The most memorable game of his high school career was the Iowa State Championship game in 1914, his junior season. The title game pitted Clinton High against West Des Moines High School, led by Aubrey Devine, Slater’s future teammate at Iowa. That game ended in a 13-13 tie.

A Hawkeye Star

In 1918, Duke Slater took to the football field at the University of Iowa, where he would achieve his greatest fame. Under the instruction of Coach Howard Jones, Slater developed into one of the greatest linemen ever to play college football. Eligibility rules in 1918 were suspended due to World War I; therefore, Slater was able to compete and letter in football at Iowa as a freshman. He was selected to the all-Iowa team as a freshman by the Des Moines Register, but his second year with the Hawks would be even better.

In 1918, Duke Slater took to the football field at the University of Iowa, where he would achieve his greatest fame. Under the instruction of Coach Howard Jones, Slater developed into one of the greatest linemen ever to play college football. Eligibility rules in 1918 were suspended due to World War I; therefore, Slater was able to compete and letter in football at Iowa as a freshman. He was selected to the all-Iowa team as a freshman by the Des Moines Register, but his second year with the Hawks would be even better.

As a sophomore in 1919, Slater was a unanimous first team All-Big Ten selection and a second team All-American. This made him the first black All-American at Iowa and just the sixth African-American to earn such honors in the history of college football. Spectators marveled at Slater’s rugged line play. Walter Eckersall, the foremost authority on college football at the time outside of the east coast, wrote, “Slater is so powerful that one man cannot handle him and opposing elevens have found it necessary to send two men against him every time a play was sent off his side of the line.” Fritz Crisler, a University of Chicago end who went on to become a legendary coach and athletic director at Michigan, said, “Duke Slater was the best tackle I ever played against. I tried to block him throughout my college career but never once did I impede his progress to the ball carrier.”

Duke Slater was again a first team All-Big Ten selection as a junior in 1920, but it was his senior season that served as the pinnacle of his college career.

The 1921 Hawkeyes

The 1921 Hawkeyes were arguably the greatest team in Iowa history. The Hawks had a perfect 7-0 record and never trailed at any point during the season. The team blew through the conference schedule to claim the school’s first outright Big Ten championship. But the team’s biggest win was a non-conference victory over Coach Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame squad. Rockne only lost 12 games as the head coach at Notre Dame; this was one of them.

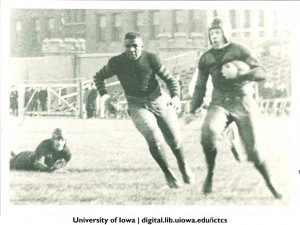

The Fighting Irish came into the 1921 Iowa game riding a 20-game unbeaten streak. The Hawks jumped on the board early with ten quick points and held on for a 10-7 upset victory. One of the greatest photographs in the history of Iowa football is from that game, depicting a helmetless Slater clearing a hole for teammate Gordon Locke by blocking three Notre Dame defenders. That victory over Notre Dame helped the Hawks on their way to their own 20-game winning streak, which is still the longest in school history.

The Fighting Irish came into the 1921 Iowa game riding a 20-game unbeaten streak. The Hawks jumped on the board early with ten quick points and held on for a 10-7 upset victory. One of the greatest photographs in the history of Iowa football is from that game, depicting a helmetless Slater clearing a hole for teammate Gordon Locke by blocking three Notre Dame defenders. That victory over Notre Dame helped the Hawks on their way to their own 20-game winning streak, which is still the longest in school history.

The Hawkeyes were the undisputed champions of the Midwest and had a legitimate claim as the best team in the country in 1921. That gave Slater’s place on the team cultural significance; it was the first time in the history of college football that an African-American played a prominent role on a legitimate national championship contender. And Slater’s role was indeed prominent. He was named first team All-Big Ten for the third straight year, still one of only nine Hawkeyes ever to have been named to three All-Big Ten teams.

More than that, Duke Slater became an All-American for the second time. Nearly every major All-American team in the country had Slater as a first team All-American. Sadly, the most prominent All-American selector at that time, Walter Camp, relegated Slater to a second team All-American, a decision that was met with considerable criticism at the time. Camp’s decision to leave Slater off of his first All-American team resulted in Duke not being recognized as a consensus All-American by the NCAA.

Nevertheless, Slater was widely praised as one of the greatest linemen in college football history. In 1946, he was one of eleven men selected on an all-time college football All-American team by a nationwide panel of voters. Five years later, Duke Slater was inducted as a member of the inaugural class of the College Football Hall of Fame. He was the only African-American elected in that first class and one of only two Hawkeye players (joining Nile Kinnick).

All in all, Slater was the centerpiece of four great Hawkeye teams. His career record in four years at Iowa was 23-6-1, and the Hawkeyes had won ten straight games at the time Slater left school. Duke Slater was also a standout on the Hawkeye track team, throwing the shotput, the discus, and the hammer. Slater and Eric Wilson helped guide the Hawkeyes to a surprising third place finish at the first ever NCAA Track and Field Championships in 1921. Slater finished third in the country in the hammer throw and fourth in the discus throw.

An NFL Trailblazer

Duke Slater joined the NFL’s Rock Island Independents in 1922, becoming the first African-American lineman in NFL history. He made his NFL debut on October 1, 1922, leading the Independents to a victory over quarterback Curly Lambeau and the Green Bay Packers, 19-14. After his rookie season with the Independents concluded, Slater joined the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers for two games at the end of the 1922 season. But he returned to the Independents at the beginning of the 1923 season and played his next four seasons – five in all – with the Rock Island club.

The Rock Island Independents’ best season in the NFL came in 1924. Bolstered by an aging Jim Thorpe, the Indees were undefeated and on top of the NFL standings a month into the season. The Independents suffered their first loss when the winless Kansas City Blues upset them on October 26, 23-7. Slater wasn’t in Rock Island’s lineup that day; he was held out of the game because the NFL had a “gentlemen’s agreement” that African-Americans didn’t participate in games held in the state of Missouri. It was the only game Duke Slater missed in his ten-year NFL career, and it wasn’t due to injury or illness…it was due to the prevailing discrimination of the time.

Two weeks later, the Blues and Independents had a rematch in Rock Island, and since the game was held in Illinois, Slater was free to play. The Independents won convincingly, 17-0, but the damage had already been done. Rock Island finished the year with two losses, one more than the NFL champion Cleveland Bulldogs.

Duke Slater became the most decorated player in the history of the Rock Island Independents. He was named an all-pro after the 1923, 1924, and 1925 seasons, the only Independent to make three all-pro teams. In 1926, the Independents dropped out of the NFL and joined the rival American Football League. Slater played one season with the Independents in the AFL before the franchise went bankrupt, along with the rest of the league.

Duke Slater became the most decorated player in the history of the Rock Island Independents. He was named an all-pro after the 1923, 1924, and 1925 seasons, the only Independent to make three all-pro teams. In 1926, the Independents dropped out of the NFL and joined the rival American Football League. Slater played one season with the Independents in the AFL before the franchise went bankrupt, along with the rest of the league.

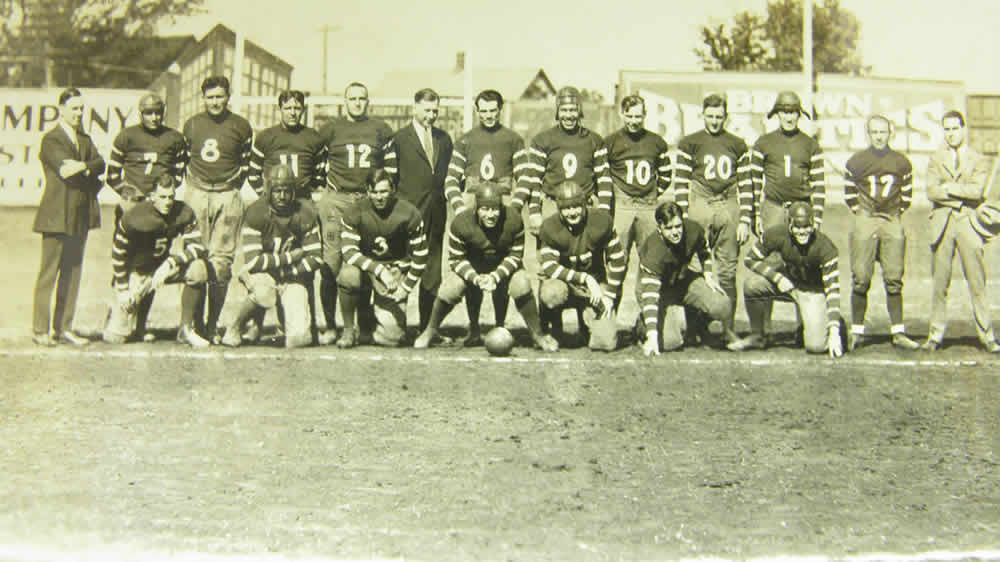

The Chicago Cardinals

When the Independents went under, Slater was immediately signed by the Chicago Cardinals of the NFL. The Cardinals occupied the South Side of Chicago opposite the Bears, who dominated the North Side. The two franchises had a heated rivalry that culminated every year in a Thanksgiving Day game for Windy City bragging rights.

African-Americans were still sparsely populating professional football, whereas they had been banned at the highest levels of pro baseball for decades. By 1927, the NFL was ready to follow baseball’s lead and ban black players from the league. However, Duke had established himself as one of the league’s greatest linemen. For most of the late-1920s, Duke Slater was the only African-American in the entire NFL. The Chicago Cardinals brought in Harold Bradley, another African-American lineman, to stand alongside Slater for two games in the 1928 season before Bradley was released. With exception of those two games by Bradley, Duke Slater was the only African-American in the National Football League from 1927-1929.

Slater made his presence count. He was the only African-American in the NFL in 1927 and 1929, yet he was named an all-pro both seasons! His greatest NFL moment came on November 28, 1929. The Cardinals squared off with the Bears in their annual Thanksgiving Day game, and Cardinal back Ernie Nevers had one of the greatest days in pro football history. Nevers set an NFL record that still stands today, over eighty years later, by scoring forty points on six rushing touchdowns in the Cardinals’ 40-6 victory. It remains the oldest individual record in the NFL’s record books. Duke Slater played all sixty minutes in that game, the only Cardinal lineman to do so.

Slater made his presence count. He was the only African-American in the NFL in 1927 and 1929, yet he was named an all-pro both seasons! His greatest NFL moment came on November 28, 1929. The Cardinals squared off with the Bears in their annual Thanksgiving Day game, and Cardinal back Ernie Nevers had one of the greatest days in pro football history. Nevers set an NFL record that still stands today, over eighty years later, by scoring forty points on six rushing touchdowns in the Cardinals’ 40-6 victory. It remains the oldest individual record in the NFL’s record books. Duke Slater played all sixty minutes in that game, the only Cardinal lineman to do so.

Duke Slater was a consistent all-pro from 1923-1930. He was the first NFL lineman – of any race – to make all-pro teams in seven different seasons. Slater earned all-pro mentions every season from 1923-1930 except 1928 – when his Cardinal team played only half of an NFL schedule due to financial difficulties – and 1926, when some NFL-only all-pro selectors omitted him because his Rock Island club played that year in the AFL. But without a doubt, Slater was a reliably dominant lineman in pro football for eight years, which was a very, very long stretch of dominance back in that era.

Slater’s longevity in pro football at the time was remarkable. When Slater retired from the NFL in 1931, his ten pro seasons ranked third in NFL history. He started 96 of his 99 career games played; those 96 starts ranked fourth in pro football history at the time of his retirement. Slater’s percentage of missed starts to games played was the smallest of any NFL player whose career ended before 1950 (minimum 80 games played). And bear in mind that he did all this despite being one of the only – and for a few years, the only – African-American players in the NFL, subject to all of the rough play that such a designation would have drawn to him.

Duke Slater’s career made a positive impact on the NFL. He single-handedly kept the door open for African-Americans in pro football and delayed a “color ban” from taking effect in the NFL for seven years. The league wanted to impose a ban in 1927, but Slater’s consistently outstanding play wouldn’t let them. It wasn’t until two years after Slater retired from the NFL that the league finally pushed through a ban on African-Americans that lasted for twelve years until 1946.

For more information about Duke Slater’s incredible impact on the NFL and his case for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, read here.

A Pioneer for His Race

With African-Americans restricted from playing in the NFL in the 1930s, Slater helped fight the color ban by coaching all-star teams of African-American players. Slater served as head coach of the Chicago Negro All-Stars in 1933, the Chicago Brown Bombers in 1937, the Chicago Comets in 1939, and the Chicago Panthers in 1940. He also served as an assistant coach for the Chicago Negro All-Stars in 1938 in a high-profile exhibition game staged at Soldier Field against the Chicago Bears. These coaching stints and teams helped give African-Americans opportunities in football and showed the public that blacks and whites could play the game together without racial incidents.

In terms of contributions to the Hawkeye athletic department, on the field and off, Duke Slater is, in my opinion, the greatest Hawkeye athlete of all time. His contributions to Hawkeye football (and track) as an athlete have been well-documented, but one of the main reasons I believe Slater is the greatest Hawkeye of them all is because of the influence he had on the Iowa athletic department in the decades after he left the field. Duke Slater remained a prominent booster of the Hawkeye football program his whole life, attending every Hawkeye homecoming game from 1935-1962, following the Hawkeyes to Chicago-area road games, and traveling to California for both of Iowa’s Rose Bowl games in the 1950s.

But more than that, his recruiting efforts changed the face of Hawkeye athletics forever. He recruited dozens of prominent athletes – including many high-profile African-American athletes – to Iowa City. Either directly through personal recruiting efforts or indirectly through his widespread fame as the greatest black football player of his generation, Slater influenced dozens of black athletes to give the Hawkeyes a chance. Ozzie and Don Simmons, Jim Walker, Emlen Tunnell, Earl Banks, Carl Cain, Sherman Howard, Harold Bradley (Sr. and Jr.), Mike Riley, Nolden Gentry, Simon Roberts…these are only a few of the athletes who knew, from Slater’s example, that the University of Iowa would give African-Americans an athletic opportunity. The school developed a reputation in that era of widespread discrimination as a “safe haven” where black players would be given a chance to compete, and more than any other individual, Duke Slater was responsible for fostering that reputation. Slater’s influence diversified the athletic department, and some of the greatest players and teams in Iowa history can be indirectly contributed to his supportive influence.

Duke Slater also served as an ambassador for his race off the field. In his NFL off-seasons, he went back to the University of Iowa and earned his law degree in 1928. He remained in Chicago after his retirement from football and began a long career as an attorney on the South Side. Slater served as an inspiration for other young African-Americans. As a famous former football player and a wealthy assistant district attorney for the city, he earned the respect and admiration of black and white audiences alike.

That admiration culminated with his election in 1948 to the Cook County Municipal Court. Duke Slater was just the second African-American to be elected as a judge in the city of Chicago. Twelve years later, Slater was the first black judge elevated to Chicago’s Superior Court, at the time the highest court in the city; he moved over to the Circuit Court of Cook County when that court was organized in 1964. He served the Windy City for almost two decades as a prestigious, respected judge, presiding over the crowded courts of the South Side. Duke Slater’s tenure as a Chicago judge refuted the ugly stereotypes that existed at the time regarding the supposed lack of intelligence possessed by dominant black athletes.

Remembering a Legend

Duke Slater died in 1966 at age 67 from stomach cancer. His wife preceded him in death by four years; they had no children. Slater’s death was mourned nationwide as a terrible loss of one of the nation’s most unique and revered sports figures. In 1972, when the University of Iowa was considering renaming then-Iowa Stadium, the president of the university at the time suggested that the stadium be renamed “Kinnick-Slater Stadium.” Some Nile Kinnick supporters objected to the idea, and so a compromise was proposed: Iowa Stadium would become Kinnick Stadium, and the newest residence hall on campus, Rienow II, would be renamed Slater Hall in honor of Duke.

Duke Slater died in 1966 at age 67 from stomach cancer. His wife preceded him in death by four years; they had no children. Slater’s death was mourned nationwide as a terrible loss of one of the nation’s most unique and revered sports figures. In 1972, when the University of Iowa was considering renaming then-Iowa Stadium, the president of the university at the time suggested that the stadium be renamed “Kinnick-Slater Stadium.” Some Nile Kinnick supporters objected to the idea, and so a compromise was proposed: Iowa Stadium would become Kinnick Stadium, and the newest residence hall on campus, Rienow II, would be renamed Slater Hall in honor of Duke.

It was a wonderful tribute at the time. But today, the effects of the compromise are still being felt. Kinnick’s name being on the stadium has elevated his fame among the Iowa fanbase to almost unimaginable proportions, while Slater has faded into relative anonymity. One of the greatest players in Iowa history – a man every bit on the level of Nile Kinnick as far as significance and impact on the Hawkeye football program during his lifetime – has fallen by the wayside, out of sight and out of mind.

Many Hawkeye and NFL fans have never even heard the name Duke Slater, and fewer still appreciate everything he did to advance the cause of racial equality in the game of football. His life story is every bit as inspirational and compelling as the stories of Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, Nile Kinnick, and others that many sports fans know by heart, but Slater has slipped into the “limbo of antiquity”. It has been my personal mission for the past few years to help correct that injustice.

One of the greatest oversights regarding Duke Slater’s legacy was his long absence from the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Slater was a Pro Football Hall of Fame finalist in 1970 and 1971, the first two years finalists were announced, but his candidacy was then overlooked for decades. I’m so pleased to report that Duke Slater was recently elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame as a member of their 2020 Centennial Class. For a quick recap of Slater’s Hall of Fame credentials, read here.

Even Duke Slater’s jersey is in the Hall of Fame in an exhibit on early African-American pioneers of the NFL, yet he’s still not a member himself.

For more information on Duke Slater, please consider picking up the book I wrote about him. There’s so much more to his story that I don’t have time to elaborate on here, but suffice it to say: Duke Slater was one of the most incredible athletes of the twentieth century.